Polar bear - Ursus Maritimus

Dec 18, 2022 12:26:34 GMT

Hardcastle, PumAcinonyx SuperCat, and 2 more like this

Post by oldgreengrolar on Dec 18, 2022 12:26:34 GMT

Polar Bear - Ursus maritimus.

Kingdom Animalia

Phylum Chordata

Class Mammalia

Order Carnivora

Family Ursidae

Genus Ursus

Species Ursus maritimus

Size.

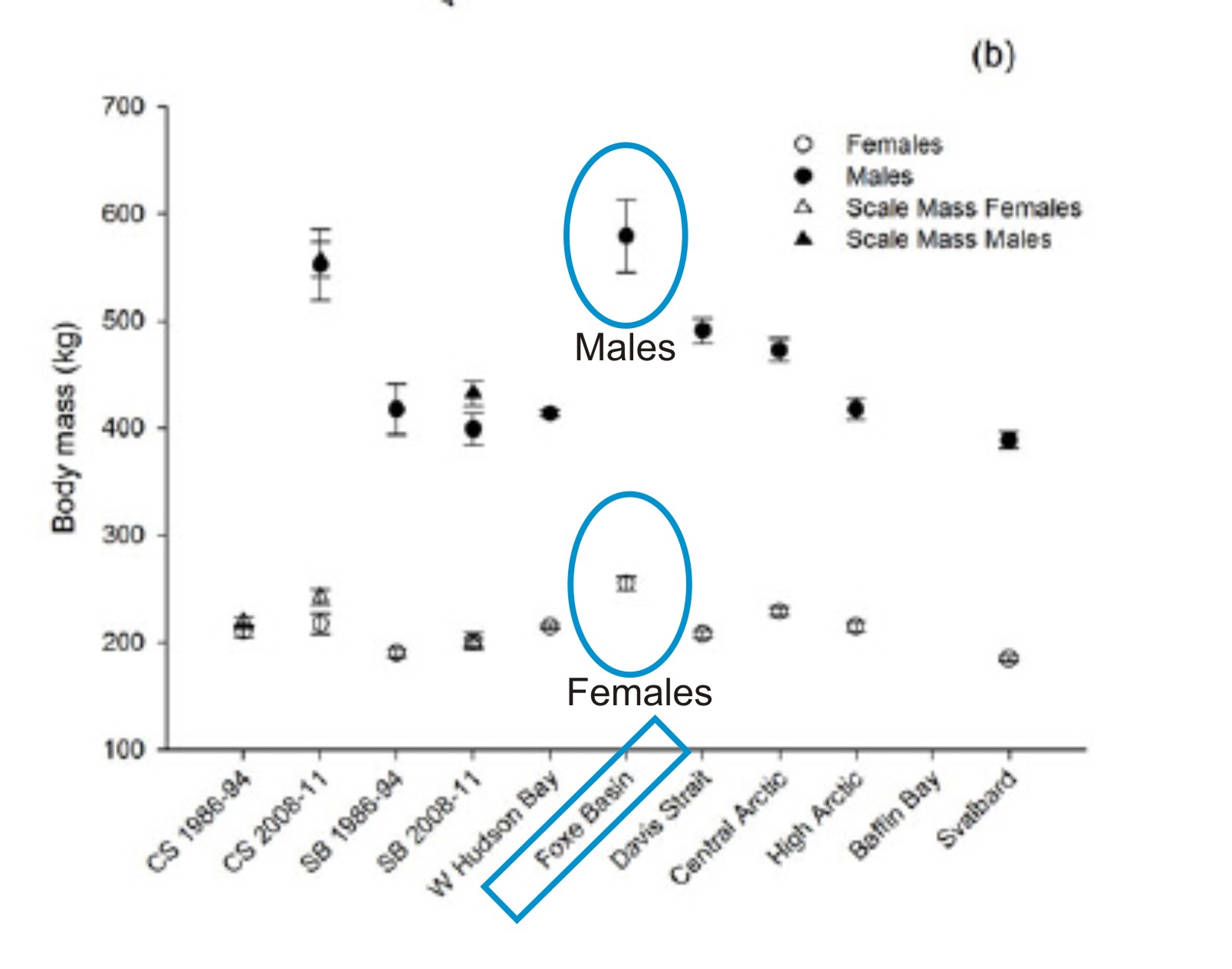

Male head-and-body length: 2.4 - 2.6 m

Female head-and-body length: 1.9 - 2.1 m

Male weight: 400 - 600 kg

Female weight: 200 - 300 kg

Description.

The polar bear is the largest living land carnivore in the world today, with adult males growing up to 2.6 meters in length. The most well known of all bears, the polar bear is immediately recognisable from the distinctive white colour of its thick fur. The only unfurred parts of the body are the foot pads and the tip of its nose, which are black, revealing the dark colour of the skin underneath the pelt. The neck of the polar bear is longer than in other species of bears, and the elongated head has small ears. Polar bears have large strong limbs and huge forepaws which are used as paddles for swimming. The toes are not webbed, but are excellent for walking on snow as they bear non-retractable claws which dig into the snow like ice-picks. The soles of the feet also have small projections and indents which act like suction cups and help this bear to walk on ice without slipping. Females are about half the size of males, although a pregnant female with stored fat can exceed 500 kg in weight. Polar bear cubs weigh up to 0.7 kilograms at birth. They look similar in appearance to adults, though they have much thinner fur.

Range.

This bear is found throughout the circumpolar Arctic on ice-covered waters, from Canada, to Norway, parts of the US, the former USSR and Greenland (Denmark). The furthest south the polar bears occur all year round is James Bay in Canada, which is about the same latitude as London. During the winter, when the ice extends further south, polar bears move as far south as Newfoundland and into the northern Bering Sea. They rarely enter the zone of the central polar basin as there is thick ice all year round and there is little to eat.

Habitat

The preferred habitat is the annual ice near the coastlines of continents and islands, where there are large numbers of ringed seals (Phoca hispida), on which these bears feed.

Biology.

Polar bears are solitary mammals throughout most of the year, with the exception of breeding pairs and family groups. Populations, or stocks, of polar bears are distributed throughout the Arctic and have overlapping home ranges which are not defended, and may vary in size from a few hundred to over 300,000 square kilometres.

Diet.

The main food source is ringed seals P. hispida, and, to a lesser degree, bearded seals (Erignathus barbatus). The polar bears capture seals when they surface to breathe, or hunt them in their lairs, where young seals are nurtured. Polar bears show some amazing adaptations to their Arctic life and are able to detect prey that are almost a kilometre away and up to a metre under the compacted snow, using their heightened sense of smell. They also feed opportunistically on walruses, belugas, narwhals, waterfowl and seabirds.

When food is available these bears have a remarkable ability to devour large amounts of food rapidly, and are also metabolically unique in their ability to switch from a normal state to a slowed-down, hibernation-like condition at any time of year when there is less food available. For example, in Hudson Bay the ice melts completely by mid-July and, as it does not re-freeze until mid-November, pregnant females do not feed for 8 months. During this fasting time, they metabolise their fat and protein stores and recycle metabolic by-products. During periods of particularly cold weather polar bears may also fast, and are known to conserve energy by occupying temporary dens.

Reproduction.

Polar bears breed from late March to late May. Females nurse and care for their cubs for 2.5 years and are therefore only available for mating once the cubs are independent, every three years. As this means that only a third of females can breed each season there is intense competition by the males for females, which may explain why males are so large in size. Females must mate many times over a period of several weeks before ovulation and fertilisation are stimulated (induced ovulation), and breeding pairs remain together for one to two weeks to ensure successful mating. If the female’s partner is displaced she may mate with more than one male at this time. Implantation of the fertilised egg is delayed until mid-September to mid-October, and the female gives birth to the young in a snow den some two to three months later. Two-thirds of litters are twins, and single litters and triplets are also born. Though the polar bear has low reproductive potential, individuals do live for a long time, and have been known to live for up to 30 years.

Threats.

Polar bears are not endangered, though if hunting was not regulated they would be, due to their slow rates of population growth. They do face threats however, that must be constantly monitored. The Polar Bear Specialist Group reported in their 2005 meeting that the greatest challenge to the conservation of polar bears may be large-scale ecological change resulting from climatic warming, if the trend documented in recent years continues. Other threats to this species include pollution, poaching, and disturbances from industrial activities.

While the effects of climate change are not certain, it is recognised that even minor climate changes can have profound effects on polar bears and their sea-ice habitat. For example, if climate change results in increased snow in the Arctic, polar bears may be less able to hunt prey by entering seal birth lairs, which will affect the survival of both polar bear adults and cubs. On the other hand, if there is reduced snow and increased seasonal rain, seal productivity may be reduced as the lairs may not be thick enough to protect the pups as they develop, or lairs may collapse and kill the seals. In turn this would reduce prey for the polar bears. Unusual warm weather could also impact the polar bear’s denning activity.

Persistent Organic Pollutants (POP) also pose a threat to polar bears. Studies on the accumulation of organochlorines (caused by pollutants) through food chains have shown that polar bears, as top predators, are at risk of accumulating elevated levels of these compounds. These levels are associated with a range of effects, including neurological, reproductive and immunological changes, which may, for example, reduce ability to fight diseases and reproduce.

In the 1960s and 1970s, extensive hunting of polar bears had pushed them to the brink of extinction. This threat had a considerable impact on polar bear populations, and, though hunting is now controlled, populations are still recovering.

_____________________________________________________________________

A large male bear emerges from the willows below a small hill as the sun begins to set. Hudson Bay area near Churchill MB.

Polar bears defy extinction threat

CHRIS MCAULEY

THE world’s polar bear population is on the increase despite global warming, which scientists had believed was pushing the animal towards extinction.

According to new research, the numbers of the giant predator have grown by between 15 and 25 per cent over the last decade.

Some authorities on Arctic wildlife even claim that hunting, and not global warming, has been the real cause of the decrease in polar bear numbers in areas where the species is in decline.

A leading Canadian authority on polar bears, Mitch Taylor, said: "We’re seeing an increase in bears that’s really unprecedented, and in places where we’re seeing a decrease in the population it’s from hunting, not from climate change."

Mr Taylor estimates that during the past decade, the Canadian polar bear population has increased by 25 per cent - from 12,000 to 15,000 bears.

He even suggests that global warming could actually be good for the bears, and warns that the ever-increasing proximity of the animals to local communities could mean that a cull will be required sooner rather that later if bear numbers are to be kept under control.

In the northern territories, where temperatures have risen an average of four degrees since 1950, wildlife experts such as Mr Taylor say the bears have never been healthier or more plentiful.

The findings fly directly in the face of recent warnings from the scientific community on the demise of the species, with the Canadian World Wildlife Fund currently speculating that the last polar bear could vanish from the earth within 100 years.

The WWF website states: "By 2100, there may be no ice left in the Arctic in the summer. That means no polar bears. Global warming - caused by fossil fuels - is to blame."

The contradicting claims on the consequences of global warming are not confined to the Arctic, however.

The situation is mirrored on the opposite side of the world, where the extent of global warming and shifting ice in Antarctica is currently the subject of debate.

Scientists looking southward from the tip of South America, over steel-grey waters towards icy Antarctica, see only questions on the horizon about the fate of the planet.

Research carried out during a recent two-month exploratory mission to the South Pole has suggested that the West Antarctic ice shelf may be much thicker that at first thought - many hundreds of feet thicker in some parts - with the potential to raise water levels by around 15 feet worldwide if the shelf should gradually melt.

The hunt for data on ice movements around the South Pole has taken on fresh urgency after Antarctica’s "Larsen B," an ice shelf bigger than Luxembourg, collapsed into the Southern Ocean over the space of just 35 days in 2002.

And now that one mammoth Antarctic ice shelf has actually collapsed into the ocean, is it possible that another, even bigger one, might also crumble and slip into an ever-warming sea?

"People don’t have the answer to the question yet - what the probability is of that collapse, if any," said a scientist Gino Casassa, an authority in global warming based in Chile.

With the potential to raise ocean levels by around five metres worldwide should the ice melt, it is little wonder that glaciologists such as Mr Casassa view developments around the West Antarctic ice sheet with concern.

Should the ice eventually turn to water it would signal a slow-motion catastrophe for global coastlines - not instantly deadly like the tsunami in Asia - but more universal and more permanent. Although stressing that all the data secured from the recent two-month trip to the South Pole was still awaiting full analysis, Mr Casassa stressed that "the deeper the West Antarctic Ice Sheet, the greater the potential impact to sea level".

But scientists concede that much remains unknown about the links between ice, ocean and skies.

It still isn’t known, for example, how excess amounts of cold, fresh water from glaciers could affect the ocean current that circles Antarctica from west to east - a main driver of all the world’s ocean currents and therefore of global climate.

thescotsman.scotsman.com/internatio...fm?id=143012005

From walruses we pass to bears. Mr.Lamont believes that the Polar Bear - the Ursus Maritimus of naturalists - is, in a state of nature, the largest and strongest carnivorous animal in the world. Be this as it may, his first specimen - the one which he was watching through the old opera-glass of which we have spoken - was a monster. His carcass measured eight feet in length, and almost as much in circumference. He stood four and a half feet high at the shoulder. The fore-paws were 34 inches around. His weight was at least 1200 pounds: of this the fat constituted 400 pounds, and the hide 100. When skinned, his neck and shoulders were like those of a bull. The hunters say that he will kill the biggest bull-walrus, although nearly three times his own weight, by springing upon him from behind, and battering in his skull by repeated blows. Mr. Lamont believes this, though he doubts the stories told of the way in which he is killed by hunters. One man, who professes to know all about it, says that the hunters use a spear having a cross-piece a couple of feet from the point. Hunter presents point to Ursus; Ursus seizes spear by cross-piece, and in trying to drag it away buries the blade in his own body, and so kills himself.

And this:

Stout as he is, Ursa maritimus has to use cunning to get a living. He relies mainly upon walruses and seals. Though quite competent to manage the biggest walrus singly, he is overmatched by a herd; and unluckily for him walruses are apt to go in herds. He can not pick up a "junger" without bringing down upon him a score of tusked cousins and uncles. Then the seals are so shrewd. In the water they do not fear him. They can outswim and outdive him. There they will play around him in a manner calculated to aggravate his feelings to the utmost. Mr. Lamont thinks he catches one in the water now and then, but he can not con- ceive how he does it. Upon the ice Ursa has the advantage. But the seals know this, and sleep with both ears and one eye open. But Ursa's eyes and nose are of the sharpest. When either of these tell him that seals are floating about on the ice he slips into the water, half a mile or so to the leeward, and paddles quietly along, with his nose only visible, until he is close under the cake of ice on the very edge of which the seal is reposing. Then one jump, and a blow of his huge paw, settles the business. Between strength and cunning Ursa manages to make a quite comfortable living, and keep himself in very good order. Three which Mr. Lamont killed yielded 600 pounds of fat. "What a thousand pities," he exclaims, "that it is not worth 3s. 6d. a pot, as in the Burlington Arcade!"

www.explorenorth.com/library/weekly/aa032201c.htm

Description: young polar bear walrus kill 2thalarctos maritimusckukchi sea russian arctic july

www.painetworks.com/pages2/cv/cv0177.html

Polar Bear v Walrus video

www.thatlitevideosite.com/video/3234

Kingdom Animalia

Phylum Chordata

Class Mammalia

Order Carnivora

Family Ursidae

Genus Ursus

Species Ursus maritimus

Size.

Male head-and-body length: 2.4 - 2.6 m

Female head-and-body length: 1.9 - 2.1 m

Male weight: 400 - 600 kg

Female weight: 200 - 300 kg

Description.

The polar bear is the largest living land carnivore in the world today, with adult males growing up to 2.6 meters in length. The most well known of all bears, the polar bear is immediately recognisable from the distinctive white colour of its thick fur. The only unfurred parts of the body are the foot pads and the tip of its nose, which are black, revealing the dark colour of the skin underneath the pelt. The neck of the polar bear is longer than in other species of bears, and the elongated head has small ears. Polar bears have large strong limbs and huge forepaws which are used as paddles for swimming. The toes are not webbed, but are excellent for walking on snow as they bear non-retractable claws which dig into the snow like ice-picks. The soles of the feet also have small projections and indents which act like suction cups and help this bear to walk on ice without slipping. Females are about half the size of males, although a pregnant female with stored fat can exceed 500 kg in weight. Polar bear cubs weigh up to 0.7 kilograms at birth. They look similar in appearance to adults, though they have much thinner fur.

Range.

This bear is found throughout the circumpolar Arctic on ice-covered waters, from Canada, to Norway, parts of the US, the former USSR and Greenland (Denmark). The furthest south the polar bears occur all year round is James Bay in Canada, which is about the same latitude as London. During the winter, when the ice extends further south, polar bears move as far south as Newfoundland and into the northern Bering Sea. They rarely enter the zone of the central polar basin as there is thick ice all year round and there is little to eat.

Habitat

The preferred habitat is the annual ice near the coastlines of continents and islands, where there are large numbers of ringed seals (Phoca hispida), on which these bears feed.

Biology.

Polar bears are solitary mammals throughout most of the year, with the exception of breeding pairs and family groups. Populations, or stocks, of polar bears are distributed throughout the Arctic and have overlapping home ranges which are not defended, and may vary in size from a few hundred to over 300,000 square kilometres.

Diet.

The main food source is ringed seals P. hispida, and, to a lesser degree, bearded seals (Erignathus barbatus). The polar bears capture seals when they surface to breathe, or hunt them in their lairs, where young seals are nurtured. Polar bears show some amazing adaptations to their Arctic life and are able to detect prey that are almost a kilometre away and up to a metre under the compacted snow, using their heightened sense of smell. They also feed opportunistically on walruses, belugas, narwhals, waterfowl and seabirds.

When food is available these bears have a remarkable ability to devour large amounts of food rapidly, and are also metabolically unique in their ability to switch from a normal state to a slowed-down, hibernation-like condition at any time of year when there is less food available. For example, in Hudson Bay the ice melts completely by mid-July and, as it does not re-freeze until mid-November, pregnant females do not feed for 8 months. During this fasting time, they metabolise their fat and protein stores and recycle metabolic by-products. During periods of particularly cold weather polar bears may also fast, and are known to conserve energy by occupying temporary dens.

Reproduction.

Polar bears breed from late March to late May. Females nurse and care for their cubs for 2.5 years and are therefore only available for mating once the cubs are independent, every three years. As this means that only a third of females can breed each season there is intense competition by the males for females, which may explain why males are so large in size. Females must mate many times over a period of several weeks before ovulation and fertilisation are stimulated (induced ovulation), and breeding pairs remain together for one to two weeks to ensure successful mating. If the female’s partner is displaced she may mate with more than one male at this time. Implantation of the fertilised egg is delayed until mid-September to mid-October, and the female gives birth to the young in a snow den some two to three months later. Two-thirds of litters are twins, and single litters and triplets are also born. Though the polar bear has low reproductive potential, individuals do live for a long time, and have been known to live for up to 30 years.

Threats.

Polar bears are not endangered, though if hunting was not regulated they would be, due to their slow rates of population growth. They do face threats however, that must be constantly monitored. The Polar Bear Specialist Group reported in their 2005 meeting that the greatest challenge to the conservation of polar bears may be large-scale ecological change resulting from climatic warming, if the trend documented in recent years continues. Other threats to this species include pollution, poaching, and disturbances from industrial activities.

While the effects of climate change are not certain, it is recognised that even minor climate changes can have profound effects on polar bears and their sea-ice habitat. For example, if climate change results in increased snow in the Arctic, polar bears may be less able to hunt prey by entering seal birth lairs, which will affect the survival of both polar bear adults and cubs. On the other hand, if there is reduced snow and increased seasonal rain, seal productivity may be reduced as the lairs may not be thick enough to protect the pups as they develop, or lairs may collapse and kill the seals. In turn this would reduce prey for the polar bears. Unusual warm weather could also impact the polar bear’s denning activity.

Persistent Organic Pollutants (POP) also pose a threat to polar bears. Studies on the accumulation of organochlorines (caused by pollutants) through food chains have shown that polar bears, as top predators, are at risk of accumulating elevated levels of these compounds. These levels are associated with a range of effects, including neurological, reproductive and immunological changes, which may, for example, reduce ability to fight diseases and reproduce.

In the 1960s and 1970s, extensive hunting of polar bears had pushed them to the brink of extinction. This threat had a considerable impact on polar bear populations, and, though hunting is now controlled, populations are still recovering.

_____________________________________________________________________

A large male bear emerges from the willows below a small hill as the sun begins to set. Hudson Bay area near Churchill MB.

Polar bears defy extinction threat

CHRIS MCAULEY

THE world’s polar bear population is on the increase despite global warming, which scientists had believed was pushing the animal towards extinction.

According to new research, the numbers of the giant predator have grown by between 15 and 25 per cent over the last decade.

Some authorities on Arctic wildlife even claim that hunting, and not global warming, has been the real cause of the decrease in polar bear numbers in areas where the species is in decline.

A leading Canadian authority on polar bears, Mitch Taylor, said: "We’re seeing an increase in bears that’s really unprecedented, and in places where we’re seeing a decrease in the population it’s from hunting, not from climate change."

Mr Taylor estimates that during the past decade, the Canadian polar bear population has increased by 25 per cent - from 12,000 to 15,000 bears.

He even suggests that global warming could actually be good for the bears, and warns that the ever-increasing proximity of the animals to local communities could mean that a cull will be required sooner rather that later if bear numbers are to be kept under control.

In the northern territories, where temperatures have risen an average of four degrees since 1950, wildlife experts such as Mr Taylor say the bears have never been healthier or more plentiful.

The findings fly directly in the face of recent warnings from the scientific community on the demise of the species, with the Canadian World Wildlife Fund currently speculating that the last polar bear could vanish from the earth within 100 years.

The WWF website states: "By 2100, there may be no ice left in the Arctic in the summer. That means no polar bears. Global warming - caused by fossil fuels - is to blame."

The contradicting claims on the consequences of global warming are not confined to the Arctic, however.

The situation is mirrored on the opposite side of the world, where the extent of global warming and shifting ice in Antarctica is currently the subject of debate.

Scientists looking southward from the tip of South America, over steel-grey waters towards icy Antarctica, see only questions on the horizon about the fate of the planet.

Research carried out during a recent two-month exploratory mission to the South Pole has suggested that the West Antarctic ice shelf may be much thicker that at first thought - many hundreds of feet thicker in some parts - with the potential to raise water levels by around 15 feet worldwide if the shelf should gradually melt.

The hunt for data on ice movements around the South Pole has taken on fresh urgency after Antarctica’s "Larsen B," an ice shelf bigger than Luxembourg, collapsed into the Southern Ocean over the space of just 35 days in 2002.

And now that one mammoth Antarctic ice shelf has actually collapsed into the ocean, is it possible that another, even bigger one, might also crumble and slip into an ever-warming sea?

"People don’t have the answer to the question yet - what the probability is of that collapse, if any," said a scientist Gino Casassa, an authority in global warming based in Chile.

With the potential to raise ocean levels by around five metres worldwide should the ice melt, it is little wonder that glaciologists such as Mr Casassa view developments around the West Antarctic ice sheet with concern.

Should the ice eventually turn to water it would signal a slow-motion catastrophe for global coastlines - not instantly deadly like the tsunami in Asia - but more universal and more permanent. Although stressing that all the data secured from the recent two-month trip to the South Pole was still awaiting full analysis, Mr Casassa stressed that "the deeper the West Antarctic Ice Sheet, the greater the potential impact to sea level".

But scientists concede that much remains unknown about the links between ice, ocean and skies.

It still isn’t known, for example, how excess amounts of cold, fresh water from glaciers could affect the ocean current that circles Antarctica from west to east - a main driver of all the world’s ocean currents and therefore of global climate.

thescotsman.scotsman.com/internatio...fm?id=143012005

From walruses we pass to bears. Mr.Lamont believes that the Polar Bear - the Ursus Maritimus of naturalists - is, in a state of nature, the largest and strongest carnivorous animal in the world. Be this as it may, his first specimen - the one which he was watching through the old opera-glass of which we have spoken - was a monster. His carcass measured eight feet in length, and almost as much in circumference. He stood four and a half feet high at the shoulder. The fore-paws were 34 inches around. His weight was at least 1200 pounds: of this the fat constituted 400 pounds, and the hide 100. When skinned, his neck and shoulders were like those of a bull. The hunters say that he will kill the biggest bull-walrus, although nearly three times his own weight, by springing upon him from behind, and battering in his skull by repeated blows. Mr. Lamont believes this, though he doubts the stories told of the way in which he is killed by hunters. One man, who professes to know all about it, says that the hunters use a spear having a cross-piece a couple of feet from the point. Hunter presents point to Ursus; Ursus seizes spear by cross-piece, and in trying to drag it away buries the blade in his own body, and so kills himself.

And this:

Stout as he is, Ursa maritimus has to use cunning to get a living. He relies mainly upon walruses and seals. Though quite competent to manage the biggest walrus singly, he is overmatched by a herd; and unluckily for him walruses are apt to go in herds. He can not pick up a "junger" without bringing down upon him a score of tusked cousins and uncles. Then the seals are so shrewd. In the water they do not fear him. They can outswim and outdive him. There they will play around him in a manner calculated to aggravate his feelings to the utmost. Mr. Lamont thinks he catches one in the water now and then, but he can not con- ceive how he does it. Upon the ice Ursa has the advantage. But the seals know this, and sleep with both ears and one eye open. But Ursa's eyes and nose are of the sharpest. When either of these tell him that seals are floating about on the ice he slips into the water, half a mile or so to the leeward, and paddles quietly along, with his nose only visible, until he is close under the cake of ice on the very edge of which the seal is reposing. Then one jump, and a blow of his huge paw, settles the business. Between strength and cunning Ursa manages to make a quite comfortable living, and keep himself in very good order. Three which Mr. Lamont killed yielded 600 pounds of fat. "What a thousand pities," he exclaims, "that it is not worth 3s. 6d. a pot, as in the Burlington Arcade!"

www.explorenorth.com/library/weekly/aa032201c.htm

Description: young polar bear walrus kill 2thalarctos maritimusckukchi sea russian arctic july

www.painetworks.com/pages2/cv/cv0177.html

Polar Bear v Walrus video

www.thatlitevideosite.com/video/3234

. Besides I apologise if the op is a bit messy. Will tidy it up tomorrow when I get on my lap top.

. Besides I apologise if the op is a bit messy. Will tidy it up tomorrow when I get on my lap top.

.

.

[/a]

[/a]